When teachers reach for help at 10.47am

Early results from aprendIA's Nigeria pilot show teachers learning in ways that align with how they actually work

Back in November, we introduced aprendIA—IRC's AI-driven teacher support programme designed to deliver evidence-based professional development via WhatsApp. We shared details about our rigorous red-teaming process to ensure safe deployment in humanitarian contexts.

Now, twenty-four weeks into our Northeast Nigeria pilot, we want to share more about what we’ve seen of people’s interactions with aprendIA. The results suggest aprendIA is meeting a real need, and doing so in ways that align with how teachers work.

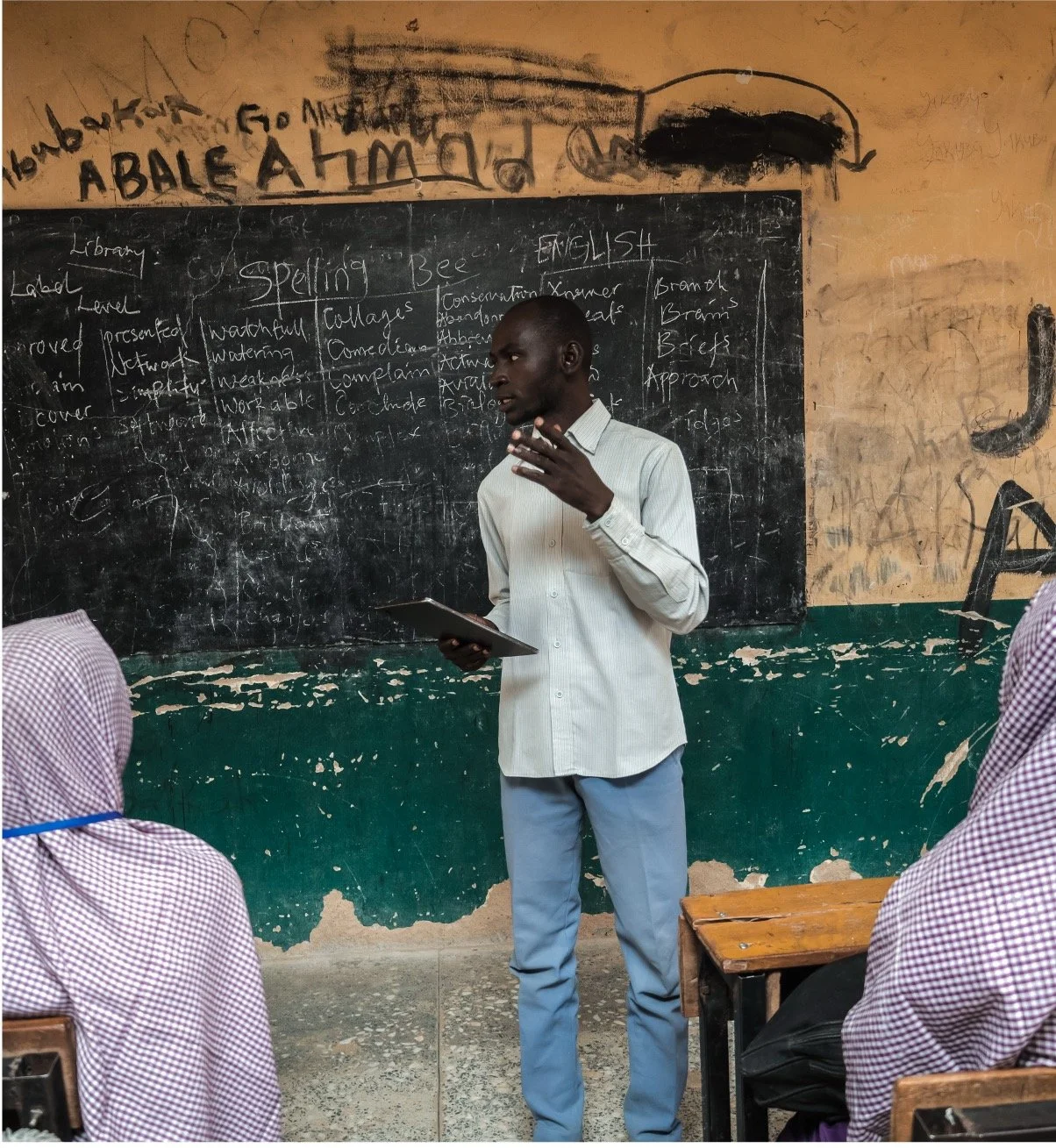

It's 10.47 on a Tuesday morning in Adamawa State, northern Nigeria. Between lessons, a teacher pulls out her phone, opens WhatsAppan app and types: "How can I calm the class after break?" Three minutes later, she's back in the classroom trying a breathing exercise the chatbot suggested. It works. The students settle faster than usual, with a few exceptions. She makes a mental note to try the call-and-response technique tomorrow. She opens WhatsAppthe app again on Sunday evening, when she's planning next week's maths lessons.

Over the past twenty-four weeks, scenes like this have played out thousands of times across Northeast Nigeria. Since August, 645 teachers have sent more than 124,000 messages to aprendIA—IRC's AI-powered teaching support chatbot—asking questions, exploring courses, seeking help when they need it. The numbers tell one story. But the patterns of when and why teachers engage tell another, one that challenges some assumptions about how professional learning actually works.

Usage clusters around two distinct windows: 10-11am during school hours, and 7-8pm in the evening. The morning surge catches teachers during planning periods or brief breaks, seeking immediate solutions to classroom challenges they're facing right now. The evening peak captures teachers at home, preparing tomorrow's lessons, thinking ahead rather than reacting. What this temporal signature reveals is that professional development, in practice, doesn't happen according to predetermined schedules or curriculum sequences—it happens when the gap between what teachers know and what their students require becomes pressing.

What Teachers Ask

Some ask urgent, specific questions:

"What's one way to make classroom rules together?"

"How can I calm the class after break?"

"Can you suggest a method for teaching English in a large class?"

Others start aprendIA's structured courses (classroom management, mathematics and reading) working through micro-learning modules at their own pace. Often teachers do both, moving between immediate questions and longer learning pathways depending on what the moment demands.

The questions reveal the daily reality of teaching in resource-constrained contexts: large classes, limited materials, students with diverse needs and sometimes recent trauma. Teachers ask them at 10.47am on a Tuesday morning or 7.30pm on a Sunday evening—whenever they see a gap between what they know and what their students need, or simply when they need support.

Classroom management dominates, which makes sense once you think about it. You can't teach reading to a class of 100 children who won't sit still. You can't introduce new maths concepts when students are still processing the disruption of conflict or displacement. Managing the classroom isn't preliminary to teaching—in these contexts it is perhaps the most fundamental form of teaching.

Over the pilot period, teachers started aprendIA's courses more than 1,400 times, with classroom management seeing over 600 module starts—far more than maths (300+ starts) or reading (300+ starts). All of which raises an interesting question: what does it mean that teachers engage so strongly with Module 1 of each course, but barely at all with Modules 2 through 5?

The puzzle of non-completion

Module 1 sees strong uptake. Module 2 drops to roughly 25% of that engagement. By Module 5, only a handful of teachers remain. In conventional professional development terms, a 2.5% completion rate might signal failure—disengaged teachers, broken content, an intervention that didn't work.

But consider what teachers in Northern Nigeria are actually doing with their time. They're not leisurely working through curricula. They're solving immediate problems: how to establish classroom routines, how to manage transitions, how to engage students with diverse needs. Module 1 addresses these foundational challenges. For many teachers, that appears to be exactly what they need. At least right now.

The question, then, isn't whether teachers have failed to complete courses, but whether the courses have succeeded in giving teachers what they came for. And here the data becomes interesting, because when we tracked 224 teachers from August through December, measuring their confidence in key pedagogical skills, we found meaningful gains precisely in the areas aprendIA emphasises:

Adapting lessons for different learning needs: +5.8 percentage points

Keeping students engaged: +5.4 percentage points

Managing large classrooms: +4.0 percentage points

These aren't transformative leaps. Teaching is genuinely difficult, and confidence in complex skills develops slowly, unevenly, with setbacks. But they're credible improvements. And they're happening despite what appear to be low course completion rates.

What does this suggest? Perhaps that teachers aren't failing to complete courses but rather succeeding at something we haven't quite learned to measure. They're extracting what addresses their immediate needs and stopping when those needs are satisfied. Course completion still indicates learning—exposure to evidence-based content, practice through structured activities, retrieval via embedded quizzes—but the confidence gains suggest that even incomplete engagement may produce meaningful improvements in teaching capability.

Or to put it differently: perhaps the relevant question isn't, "did they finish the course?" but, "do they have access to useful knowledge when they need it?” Or, “does that knowledge help them address genuine classroom challenges?” And, “do they remember the tool exists when new challenges arise?" And here patterns of engagement with the tool seem a useful measure.

The pattern of return

Half of teachers who stop using aprendIA later come back. Sometimes weeks later, sometimes when the term changes, sometimes when a new challenge emerges—teaching a different grade level, managing a particularly difficult class, trying to implement a new curriculum requirement. They ask new questions, perhaps explore a module they skipped before, then disappear again. This isn't linear progression through a curriculum. It's episodic engagement driven by emerging needs.

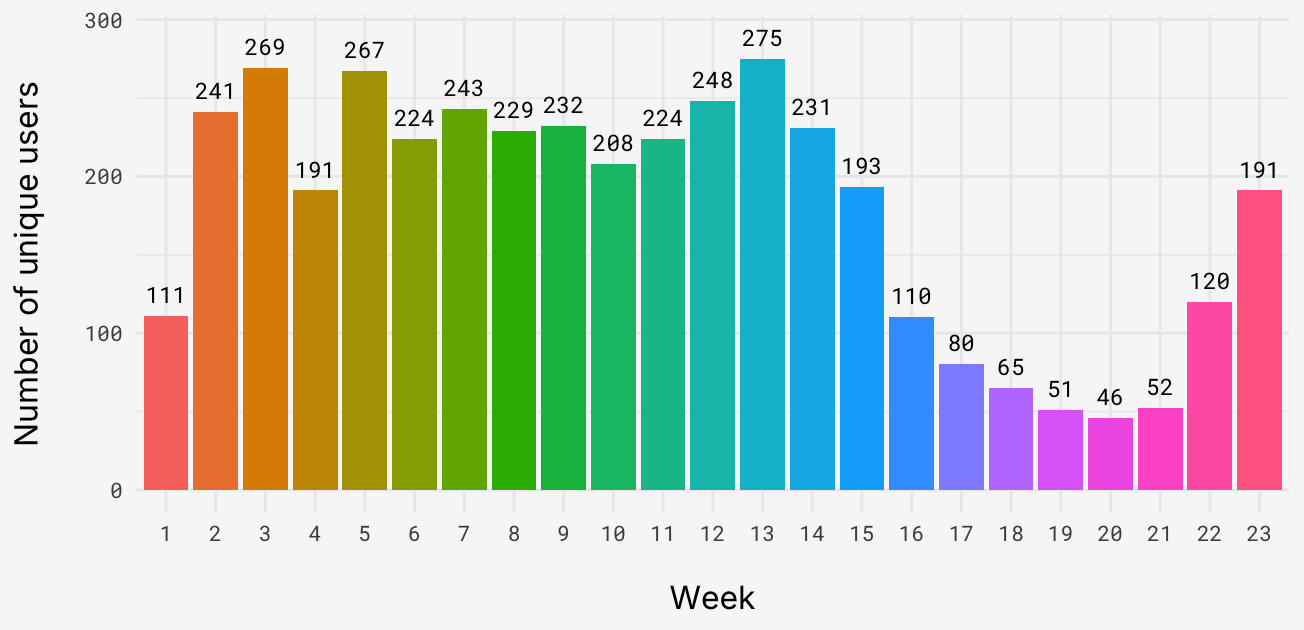

The Christmas and New Year holiday provided a natural test of this pattern. Usage dropped sharply in mid-December, falling below 100 active users for the first time since launch—down to as few as 46 users in some weeks. Then, when school resumed in January, it rebounded nearly three-fold, particularly among the teachers who had demonstrated the most intensive engagement throughout the pilot. They stopped using aprendIA when they stopped teaching, and resumed when teaching resumed.

What does this seasonal rhythm mean? It could be read as abandonment—teachers losing interest, the novelty wearing off, the tool failing to sustain engagement. But it could also be read as integration. When a tool becomes genuinely embedded in professional practice, usage follows the rhythm of that practice. Teachers use aprendIA when they're teaching, when classroom challenges demand support, when they're preparing lessons. When they're on holiday, when there are no classes to manage or lessons to plan, they don't need aprendIA. The fact that they remembered it existed and returned to it when school resumed suggests the value proposition, once established, endures even through weeks of non-use.

What teachers value

When asked what they value most about aprendIA, teachers talk about practicality: help with classroom management, lesson planning support, having tangible answers when needed. The AI has become invisible, or rather it's become what all good technology should be, a transparent medium for getting things done, unremarkable in its operation, remarkable only in its availability.

The satisfaction data reinforces this. Among the 224 teachers surveyed at both baseline and endline, 84% would recommend aprendIA to other teachers (up from 80% at baseline), 85% plan to continue using it, 82% find it useful for lesson preparation, 82% find the content relevant to their teaching. Additionally, teachers are voting with their time, which is genuinely scarce in any context, especially in crisis-affected regions where teachers often work in under-resourced schools while managing their own economic precarity.

And teachers express genuine appreciation:

"aprendIA has transformed my teaching experience. My students are learning better, behaving better, and I am more empowered as a teacher." — Samuel, Borno State

"Thank you, IRC, for this solution that strongly supports teachers like me, saves my time, and has truly been a transformative tool." — Yagana, Borno State

"aprendIA is truly a game changer for educators. It came at the right time to support teachers like me." — Hussaina, Adamawa State

The human infrastructure

One finding stands out for its implications: formal onboarding matters, perhaps more than we initially recognised.

Among teachers who used aprendIA most intensively over the pilot period—those who sent hundreds of messages across dozens of sessions—about twice as many had attended a brief orientation workshop during the first three weeks than among less engaged users. These weren't elaborate training sessions. Just simple introductions: here's what this is, here's how it works, here are some other teachers already using it.

But that initial human contact appears to have made all the difference. Teachers who participated in formal registration workshops were more likely to explore courses, ask diverse questions, develop sustained engagement patterns. Among formally registered users, 38% went on to demonstrate intensive, sustained use compared to only 22% of unregistered users.

The chatbot itself is technically accessible to anyone with WhatsApp—it works on low-bandwidth connections, requires no special apps or training, no particular technical sophistication. But accessibility, it turns out, isn't the same as adoption. And adoption isn't the same as integration. Teachers needed that human scaffolding to understand not just how to use aprendIA but why they might want to—what role it could play in their practice, what problems it might help solve, whether people they trusted considered it legitimate.

The orientation workshop provided social permission, clarified expectations, created a reference point. A workshop they remembered, faces they recognised, a sense that this tool was endorsed by people whose judgment mattered. Technology that genuinely scales, it turns out, still requires humans. The infrastructure isn't just servers and AI models. It's also workshops and peer networks and trusted intermediaries who can say: this is worth your time.

The first day

About one-third of teachers who try aprendIA once never return. They send a message, receive a response, and then the chatbot sits silent in their phones, unused. We don't yet know exactly what differentiates that first interaction for teachers who return versus those who don't. Was the answer they received helpful? Too generic? Confusing? Did they simply lack time to explore further, or mental space to consider whether this tool might be useful beyond that single query? Had they not had the chance to go to an orientation session?

Whatever happens on day one determines whether aprendIA becomes part of a teacher's practice or gets dismissed as another technology that doesn't understand their reality. Teachers who make it past that first day show dramatically different patterns. The value proposition, once established, appears to endure—even through Christmas holidays when usage drops to near-zero, then rebounds when school resumes.

This suggests the critical intervention point isn't week five or week ten, when we might think about re-engagement strategies or additional training. It's day one. And that initial experience is shaped not just by the technology—the quality of the responses, the usability of the interface—but by the human context surrounding it: the workshop that introduced the tool, the peer who recommended it, the sense of permission to try something new in an environment where innovation can feel risky.

What we don't yet know

These months of data validate proof of concept: teachers in crisis-affected contexts will use accessible, evidence-based professional development that meets them where they are—both technologically and temporally. The combination of meaningful confidence gains, high satisfaction, strong course engagement, and usage patterns that reflect genuine integration into teaching routines suggests aprendIA is addressing a real need. Teachers return to it after breaks. They come back when new challenges emerge. They recommend it to colleagues.

But proof of concept isn't proof of impact, and we should be clear about what remains unknown.

We don't yet know whether these reported confidence gains translate to changed teaching practice in actual classrooms. We don't know whether changed practice, if it exists, translates to improved student learning outcomes. We don't know whether effects persist over longer time periods, or whether they're driven primarily by novelty that will eventually fade. We don't know whether aprendIA works because of the specific content it delivers, or simply because it provides teachers with any kind of structured support and attention in contexts where both are scarce.

A rigorous impact evaluation planned for September 2026 will investigate these questions through classroom observations, student assessments, and controlled comparisons between teachers with and without access to aprendIA. It will measure not just what teachers report feeling but what they actually do in classrooms, and not just what they do but what their students learn as a consequence.

For now, we have suggestive evidence: teachers use aprendIA, value it, report confidence gains in areas the training emphasises, and return to it episodically when their work demands it. That's enough to justify continued investment and careful expansion. It's not yet enough to declare victory, or even to be confident we fully understand what's working and why.

A different model

The teacher in Adamawa State, the one who asked about calming her class after break, still hasn't finished Module 2 of classroom management. On Thursday evening she'll open aprendIA again with a question about teaching subtraction. She won't think of herself as failing to complete a course. She'll think of herself as solving tomorrow's problem.

And perhaps that's what professional development should look like, a resource to consult when the gap between what you know and what your students need becomes impossible to ignore. Not a curriculum to complete, but knowledge to access when classroom reality demands it.

The patterns from Northeast Nigeria suggest teachers might be teaching us something about how learning actually works: episodically, opportunistically, driven by genuine need rather than predetermined sequences. They're learning on their own terms, which may be the only terms on which sustainable professional development can actually happen.

Whether this model produces better teaching, and whether better teaching produces better student learning—these questions remain open. But twenty-four weeks in, we're learning that teachers know when they need help. And when we make that help available at 10.47am on a Tuesday morning, in a format they already use, with content that addresses their actual challenges, they reach for it.

That seems, at minimum, like progress worth understanding better.